Sept 17, 1999 was a Friday. At the end of a long day's work, Della Adams, information systems director for the Memphis Chamber of Commerce, knew that the Friday rush was cutting in at her parent's Chinese restaurant, where her help was needed.

Feeling "a sense of recklessness and dread" on her way, she arrived at the restaurant to discover that her 70-year-old father, who had suffered emphysema for years, "was not moving like he usually did".

She suggested closing but he refused. Two hours later he finally agreed, but insisted that they clean up first. "That was when he started to have the attack," said Adams, who, after calling 911 three times with no response, found herself driving a hundred miles an hour on the interstate highway trying to get her father to hospital.

Minutes away from the hospital, Clarence Adams, 70, fell over into his daughter's arm and said, "Della, I'm not going to make it this time."

For Della Adams, 62, the concept of her father "not going to make it" might not have existed. After all, this was a man who had survived a war that killed almost 40,000 Americans, a man who severed his festering toes in a POW camp to stop the infection from claiming his entire foot, a man who in effect was put on trial for treason yet opted to defend himself without the help of a lawyer, a man whose desire for a better life was, in his own words, "greater than any fear".

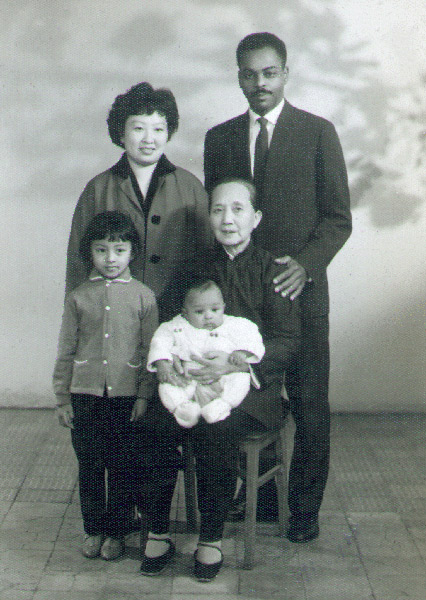

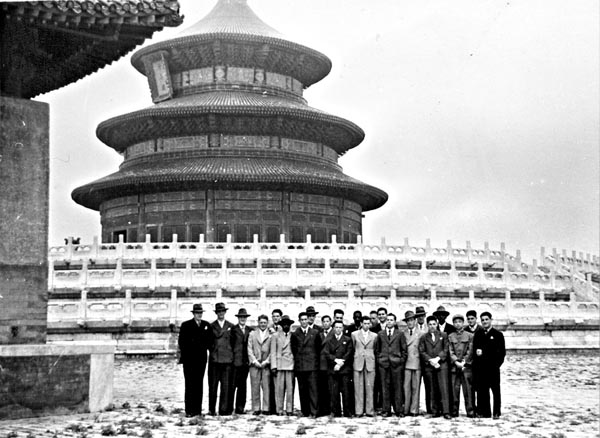

Clarence Adams, one of the 21 American POWs who refused repatriation and instead went to China in 1954 after the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea (1950-53), often referred to as the Korean War in the West, ended, remains a controversial figure at home. He returned from China to the US with his Chinese wife and children in 1966 and lived for decades with the stigma of a turncoat.

Yet for Della Adams, her father was a hero, "a man of conviction who lived his life without compromise, regardless of the consequences". This is to quote directly from an introduction written by her for the 2007 book Clarence Adams: An American Dream.

It is co-edited by her and Lewis H. Carlson, a history professor and author who first approached the former for an interview not long after her father died. Told in the first person, the book, which combines the protagonist's own writings and audio recordings with recollections of his wife and daughter, was written in words "that are certainly my father's", Adams says.

One word that surfaces from time to time and provides a dark, unsettling undercurrent to the narrative is racism. The book begins with depictions of the discrimination experienced daily by a black boy growing up in Memphis, Tennessee.

"We were allowed to shop on Main Street, but we could not eat anywhere or use a toilet," he said. One time, when a 12-year-old Adams was peeing in an alley behind the main street, he was spotted by the police and had to walk away while "peeing right down" in his own shoes.

"I might not have known what China was really like before I went there, but I certainly knew what life was like for blacks in America, especially in Memphis," Adams said years later, in defense of his life-changing decision.

The segregation was total: black teachers taught only black students; black doctors treated exclusively black patients; and black mailmen delivered mail only to blacks. Adams, who called himself "small but tough", received boxing training yet was only allowed to fight other blacks in the ring. (Years later he would take part in a bout held inside the POW camps as the war raged on. And that was more than a decade before he taught the same skills to his daughter so that she could fight off another version of racism in a place her father called home.)

In the 40s the teenage Adams, nicknamed Skippy because of his happy-jumpy nature, learned to hop trains for fun. "We would not just run up and hop on-we had to do it with style," he said.

Once, while doing his "swinging and hooking", a friend of Adams hand-slipped and landed under the train. "There he was. His body was lying on one side of the train and his legs on the other," said Adams who, if not for a series of events that took place not long afterward, might have met a similar fate.

"My father joined the army on Sept 11, 1947, at the age of 18," Della Adams said. "The day before, he had a rather violent clash with a neighborhood bully in the morning, before he and his pals ran into trouble with a white tramp asking them to find him a black woman."

The next day police banged at the front door. Getting a peek of the two policemen from the kitchen, Adams ran out the back door and kept running along the railway track until he arrived at an army recruiting station. Then and there he became an American GI.

Military life may have lifted Adams from the swamp of his previous existence, but offered little in terms of equality. He traveled with the army to the North, where "Whites Only" signs hung outside restaurants, only to be humiliated when waiters pointedly ignored him, an incident recounted with great indignation in the book.

He was shipped out to Korea and then to Japan. But there was no respite from racism since the military itself was segregated. In the summer of 1950 he was back to Fort Lewis, Washington, to be discharged. That was when President Harry Truman announced the outbreak of the war.

The horror of war dawned on Adams the moment he arrived at the front in Korea in August 1950: fellow soldiers were "blown into bits" amid raining mortars; a guy who a minute ago had prayed for life and suggested that Adams do the same "quietly fell on his side" at "a slight popping sound".

But it was not until the Chinese army crossed the border Yalu River into Korea in October 1950 that Adams started to feel imminent doom. " (They) almost wiped us out," he said. A month later Adams, after having been on a desperate run with a fellow black soldier, was captured by a Chinese soldier "staring down at us" from outside their hiding ditch.